December 31, 2020

It seems that 2020 has checked its watch, and realized it better hurry up and get its last licks in. So far, this heartbreaking year has taken about a dozen of my colleagues by means of the COVID virus, and about as many more by various other causes. That’s a couple dozen people I’ve played music with, and never will again. Other friends have survived COVID, but with lasting damage. Another dear friend has been put in a mental hospital. And now, in the waning hours of the year, comes one more, particularly devastating loss: Frank Kimbrough, one of my oldest friends in this art form.

When I got the unbearably shocking news of his death yesterday, I just sat on the couch and cried. Then I hid under a blanket. After a couple hours of this, I tried to watch an old movie. Finally, unable to avoid it any longer, I went out to my Lab at around 4 AM and recorded a solo tenor improvisation for Frank. When I can bear to listen to it, I’ll put it out there somehow.

I knew Frank before there was a Maria Schneider Orchestra. Before either of us moved to New York. Ron Horton just reminded me that I told him about Frank, and suggested they get in touch, back when Ron and I lived in Boston (years later the two of them became co-founders of the Jazz Composers Collective). So Frank and I go way back. Neither of us could remember exactly how we met – probably at some Washington, DC jam session – but it was some time in 1979 or ’80. He always spoke fondly of our first gigs, at the Boar’s Head Inn somewhere in VA, where I would show up in my 1949 Plymouth loaded with instruments.

After we both ended up in New York, he landed a steady piano gig at The Village Corner on Bleecker Street (“At the Corner of Walk and Don’t Walk”), where he held forth for years, playing solo for an assortment of drunks, characters, and – sometimes – music fans. I used to pop in there and see him, and we would chat. He had an edge in those days, an irritable side, that noticeably mellowed out when he married his wonderful Maryanne. He seemed a much happier person after that, more relaxed about life, although he kept his BS meter finely tuned and always at the ready.

I can’t recall if I had a hand in bringing Frank to Maria’s attention or not, but he became a tirelessly loyal collaborator for some 30 years — as indispensable to her music as Hodges was to Duke. I have so many pictures in my mind of the two of them hunched over the piano, figuring out how to stop the strings and where, and with what materials, to get the many otherworldly effects heard in the Winter Morning Walks project with Dawn Upshaw.

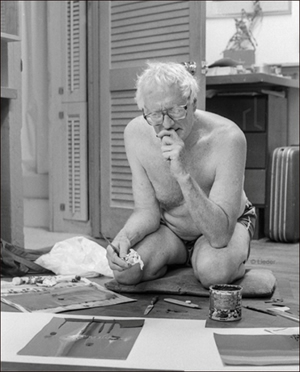

Frank did everything his own way. He never owned a cellphone. He never practiced, believing in “saving it for the gig.” Frank’s political views were decidedly liberal, and some of the ways he expressed those views were legendary. Few of us in the band will forget his refusal to cut his hair for the entirety of G.W. Bush’s 8-year tenure in the White House. But his outrage at its current occupant was beyond even the ability of such an act to express. I regret that Frank did not live to see “that fool,” as he often called him, thrown out of there.

When I built my studio, ScienSonic Laboratories, Frank was one of the first people I invited to come out and record an album of improvised duets. Normally very fussy about pianos, Frank readily agreed even though I only had a medium-size piano (“Hey, it’s still a Steinway”)… and he even consented to play some electronic instruments like Hammond and Farfisa organs, something he normally would not even consider (I recall him leaving a rehearsal once when the only available instrument was an organ of some kind). So in August of 2010 we spent a day in the Lab and recorded our album Afar, which is something very different than anything else we had done together. Most of our live duo performances consisted of tunes, and we had developed a way of moving in and out of tunes which involved a very special kind of communication which I can honestly say only happens with a very few people. That’s part of what hurts so much: I’ve not only lost a friend, but I’ve lost that music — the music that only happens when I play with that person. Unfortunately those very special tune-based duet evenings were never really documented, although we had talked of recording one.

When Frank tapped me to record, with Rufus Reid and Billy Drummond, a mammoth 6-CD set of all known, surviving Thelonious Monk compositions, I was stunned. What an incredible opportunity to learn, grow, and play great music with great people. We had an amazing six days of music and camaraderie out at “Maggie’s Farm” in rural PA, and managed to get good takes of all 70 tunes. The hang and the vibe were as good as the music. I will always be grateful for that experience. One of my favorite tracks from the project, though, is one of the few I don’t play on: Functional, a little unaccompanied blues piano gem. I was moved to write to Frank about it: “I don’t know too many cats who can play like that. Has that hint of stride feeling, but very relaxed…completely unhurried, creative and beautiful. I honestly don’t know too many pianists who could pull something like that off.”

There are so many regrets when someone like this leaves. The unsaid words. The unfinished projects… the ones discussed but not yet begun. The missed opportunities that now will never come again. One of those that will haunt me for a very long time came when the Monk group was scheduled to perform a livestream from Smalls — as my own quartet had done a couple months before, in an empty club – for Monk’s birthday in October. Three weeks before the gig, we were told there would now be an audience of 20… and I got nervous. Much as I desperately wanted to play, I asked the others if this was really a good idea. Rufus seconded my concerns, and nobody wanted to do the gig if I wasn’t comfortable about it. Frank took a raincheck from Smalls, telling me, “Don’t give it a second thought. We can do it at another time, a better time… a safer time.” Then we were offered another date in late November, again with the audience, and the COVID situation wasn’t any better. This time I was really in agony over it, and suggested that maybe they should just do the gig with another horn player. Frank wouldn’t hear of it. “We can’t do it without you,” he said. “I can’t imagine you not being there.” So those gigs didn’t happen, and despite his optimism, now they never will… and I must live with the fact that my fears of COVID took away my last two chances to ever play music with Frank Kimbrough, and with that wonderful group.

Now, as I look out the window and watch the sun finally set on this year of heartbreak and death, I find it is my unhappy turn to say, after 40 years of friendship and music, “Frank… I can’t imagine you not being there.”

Scott Robinson, New Year’s Eve 2020